Stories by Sixth Division Marines

My Time as a Marine

Chapter Six: The Battle of Chosin Reservoir

Surrounded

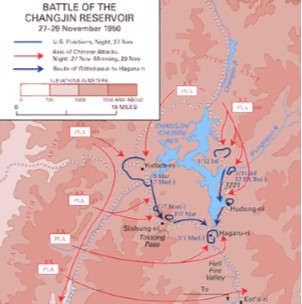

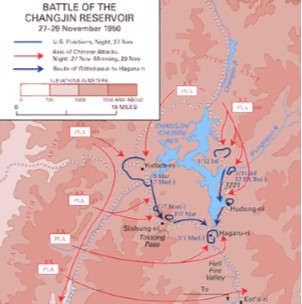

What is now known as “The Most Epic Battle in Marine Corps History” began on the night of 27 November 1950 when Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) attacked all UN Forces in North Korea. We now faced a new war against a new and powerful enemy. Ten Chinese divisions surrounded and were ready to destroy the isolated outposts of Marines one by one. Our survival, as well as most UN forces in North Korea, was suddenly in jeopardy!

I was with the Marines at Yudam-ni, which was the furthest the Marines advanced into North Korea, when the Chinese suddenly appeared and surrounded all UN Forces in North Korea. Their orders were to annihilate the 1st Marine Division to the last man. They were seasoned combat troops, having fought the Japanese, as well as the Nationalists in the recent civil war.

Around 10:00 p.m. on 27 November, we saw flares and heard bugles and whistles. The Marines inflicted heavy casualties upon the waves of attacking Chinese, but Marine casualties were also great – more than 500 wounded were brought into our area the first night. We cared for some of them in tents, but others had to stay outside in sleeping bags where the temperature had dropped to 30 degrees below zero. Blood froze, which prevented many wounded Marines from bleeding to death, but blood plasma also froze. Corpsmen thawed morphine vials in their mouth. The Chinese attack was such a surprise that many Marines were bayoneted in their sleeping bags – moisture from their breath had frozen the zippers.

Ridge Runner

The attack was stopped just 200 yards from our artillery battery. We loaded several hundred wounded and dead onto vehicles and formed a convoy. I became a “ridge runner” walking the ridge to guard the convoy from an enemy flank attack. I picked up a Garand M-1 rifle, a reliable weapon which had been left by a wounded or dead Marine. How I must have looked wearing a cartridge belt with ten clips (eight bullets each) of ammunition around my waist and a bandolier with another ten clips over each shoulder, plus four hand grenades dangling from my chest! That alone should have scared the bravest Chinese soldier.

The Chinese failed to destroy the Marines on the west side of the reservoir as the Chinese general had planned. Their intelligence forces were not aware that the 5th Regiment had joined forces with those on the west side and were thus a greater force than the general had expected.

Artillery to Infantry

Instead of being home for Christmas, as General McArthur had promised, our survival – as well as that of most UN forces in North Korea – was suddenly in jeopardy. We were at risk of annihilation! An order was issued for all units to provide men for the infantry. The even numbered gun crews from Love Battery were selected. I was on gun number one. We found we could only man four of the six guns.

The “cannon-infantry” men were sent to the top of Hill 1542, which commanded the road below, the road that was vital to our escape. The lieutenant in charge remained in a warm tent at the base of the hill, leaving Sgt. Jim Johnson to command the unit designated as Jig Company 7th Marine Regiment.

Around 4:30 a.m., a large force of Chinese wearing U.S. Marine parkas attacked Jig Company. The Marines held their fire, not knowing who they were until they were upon them. That was when they discovered that their carbines would not fire in such cold weather. Several Marines were killed and the unit was in danger of being overrun when Sgt. Johnson, realizing the situation was hopeless, gathered all the grenades. While he held off the attacking enemy, he ordered a withdrawal of the remaining force. He was last seen alive in hand to hand combat. For his actions in saving so many lives, he received the Medal of Honor posthumously.

Our howitzers had to fire at a very high angle due to the short distance to the target. It was probably the highest angle ever fired by a 155mm howitzer. Several howitzers were damaged when in recoil they hit the frozen ground. We found it necessary to somehow dig or blast a “recoil pit.” It was probably the first time in Marine Corps history.

We fired on villages to the north occupied by the Chinese, but with no visibility, results were unknown. After we fired the last of our ammunition, we hitched the guns to the prime movers and became infantrymen.

Frozen

Twice I encountered a group of Chinese soldiers barely visible in the falling snow. I fired a clip (eight bullets) at them, but I was unable to keep them in sight, and they did not return fire. It was difficult walking the steep banks in the deep snow and my frozen feet were in extreme pain. Our boots were made of rubber, totally inadequate for such cold. They had half-inch-thick felt insoles to absorb perspiration. The insoles froze, and it was like walking barefoot on ice. Whenever possible, I tried to dry out the felt insoles, each time cracking ice or frozen perspiration from my toes. Our breath and tears froze. All who served at Chosin suffer from long term cold injury, including nerve damage and pain that intensifies with age.

Toktong Pass

Seven miles south of Yudam-ni was Toktong, a vital mountain pass which was held by Fox Company of the 7th Marines. It was commonly called “Fox Hill.” Surrounded, the only way Fox Company could be supplied was by air drop. Several times the parachutes drifted into Chinese territory. Fortunately, one battery of 105mm howitzers in Hagaru-ri could support them by firing maximum range.

Fox Company was unable to treat or evacuate their wounded. Since they could not dig foxholes in the frozen ground, they stacked dead Chinese like sandbags for protection. They decimated almost an entire Chinese division while holding the pass, until a force from Yudam-ni was able to reach them. Guided only by the stars at night and a compass during the day, a relief column led by Lt. Col. Ray Davis marched through waist-deep snow around the back side of the mountains until they reached Fox Hill. The road from Yudam-ni was then cleared by taking the hills on each side of the road.

With the road cleared, our convoy left Yudam-ni on 1 December and arrived at the pass a few hours later. We loaded the wounded and dead aboard trucks. It was one of the most difficult things I have ever done. The dead bodies were frozen in the position in which they died. Reluctantly, I gave my sleeping bag to a wounded Marine. There would be little chance for me to sleep anyway until we reached Hagaru-ri. We would fall asleep walking and wander off the road, or doze off in the middle of a sentence while talking. I would sit on my helmet, which had a round bottom, and as I fell asleep I would fall over and wake up. While asleep, I would feel warm and totally at peace; I believe that is how it feels just before you freeze to death.

On to Hagaru-ri

From Toktong Pass it was about eight miles to Hagaru-ri at the base of the reservoir. Five inches of new snow had fallen. The Chinese had destroyed all the bridges and blown out sections of the mountain road. The narrow road was a sheet of ice. Again, I became a ridge runner to protect the convoy from ambush. There were times that I could not walk the flanks due to the terrain and had to walk the road. I remember a Chinese heavy machine gun firing at me from across a valley. I could see that his bullets were hitting the snow bank over my head, but I was too exhausted to care, so I continued to walk while he kept firing, never realizing that his sights were off.

We lost one truck when it slipped off the icy road and down a steep hill side. We had to burn it to destroy what we could not salvage. One truck loaded with wounded that was pulling a trailer loaded with wounded slid over the side and down a steep embankment in the middle of the night killing several of the wounded. They had to be brought back up to the road and placed wherever there was a place in the convoy, such as on a hood or fender or even on top of other wounded.

As we moved, I found myself near the end of the column. This is where the howitzers were – to prevent them from blocking the road if they became disabled. About midnight, just short of Hagaru-ri, some of the prime movers (tractors) pulling our guns ran out of diesel fuel, creating a gap in the column and the opportunity the Chinese had been waiting for.

First, they knocked out a tank from Hagaru-ri that had been sent to assist us at a bridge over an inlet, effectively blocking the road. The tank was burning, and ammunition was exploding. The flames cast a glow to the advantage of the Chinese. They went after the howitzers, firing at the tractor drivers and into the radiators. I was blinded by the flash of my first shot and I could only fire into the darkness where I thought the Chinese were. We killed several Chinese, but we also suffered casualties. I left our tractor driver for dead in the roadside ditch, but he showed up later in not much of a forgiving mood. I still bear a feeling of guilt for this.

We had to abandon nine guns by pushing them off the road. Then to reach Hagaru-ri, we had to run past the exploding tank. At first light, the British 41 Commando tried to retrieve the howitzers, but the Chinese drove them back. Army fighter planes attempted to drop napalm on them but missed. The Chinese now had nine of our eighteen 155mm howitzers, including my gun and all of my possessions.

Going back to the evening of 27 November, the Army 31st Regimental Combat Team relieved the 5th Marines on the east side of the reservoir, which allowed the 5th Marines to join the 7th Marines on the west side of the reservoir. A large force of Chinese attacked the Army units on the east, and for several days the Army engaged the Chinese force that would have otherwise been available to attack Hagaru-ri. In my opinion, this effectively kept the Chinese from seizing Hagaru-ri before the Marines from Yudam-ni were able to get there, and the Chinese were prevented from achieving their strategic objective to trap and annihilate all UN forces at Chosin.

Task Force Faith

The Army was ordered to form a force to fight their way to Hagaru-ri. Known as Task Force Faith, after Lt. Col. Don Faith, they loaded their wounded aboard trucks and decided to run the road blocks to reach Hagaru-ri. The lead truck was knocked out at the first road block, effectively blocking the road. The trucks that followed, which were carrying the wounded, attempted to go around it but were stopped. The Chinese converged on the trucks, machine gunned them, and set them on fire.

An attempt by Army tanks from Hagaru-ri to reinforce Task Force Faith had been turned back, and the Army unit that Task Force Faith was expecting to meet up with at Hudong-ni was not there. It had been withdrawn earlier to help reinforce Hagaru-ri.

Task Force Faith was effectively defeated, and each man was on his own. They were forced to abandon everything, including quad 50 caliber machine guns and twin 40mm anti-aircraft guns that had been extremely effective against the Chinese. About 400 able-bodied men and 1,500 wounded drifted into Hagaru-ri a few at a time. They either walked through the hills in waist-deep snow or over the frozen reservoir. Lt. Col. Faith was not among them.

Task Force Drysdale

Hagaru-ri was badly in need of reinforcements to hold until the Marines from Yudam-ni arrived. In a desperate attempt to help, a task force from Koto-ri, some ten miles south, was ordered to attack north to Hagaru-ri. Named Task Force Drysdale after the British commander of the Royal Marines, it was made up of the British 41 Commando and elements of the 1st Marine Regiment. They managed to reach a point half way between Hagaru-ri and Koto-ri where – at what was to become known as Hell Fire Valley – the Chinese ambushed the force, killing and wounding a large number. Numerous vehicles, including tanks, were destroyed and blocked the road, most in a jumbled heap. Some Marines ran out of ammunition, and the Chinese took them prisoner. Drysdale radioed General Smith at Hagaru-ri of the situation. He asked if he should turn back or try to get through with the remaining force. General Smith’s orders were to continue the attack “at all costs,” which they did. Of the 900 who left Koto-ri, 400 made it to Hagaru-ri.

Attack on Hagaru-ri

The Chinese had broken thru the defense perimeter of Hagaru-ri the night before we arrived from Yudam-ni, but they were driven back by a counterattack. Hagaru-ri was in danger of being overrun a second time, which would have proved fatal. That’s when 2nd Lieutenant Dick Carey sent out two South Koreans in Chinese uniforms to mingle with the Chinese in an attempt to find out where and when the next attack on Hagaru-ri would take place. They returned with the information, and the perimeter was reinforced. The Chinese attack came at the place they had determined, but it was off by one hour. Lt. Carey took a lot of kidding for failing to find out if the Chinese were on daylight savings time.

Hagaru-ri road block

In the attack, the Chinese suffered heavy casualties and were unable to penetrate the reinforced defense. The intelligence probably saved Hagaru-ri and the lives of thousands of Marines. However, Hagaru-ri would still be extremely vulnerable until the Marines from Yudam-ni arrived.

Magnificent Bastards

The first contingent of Marines from Yudam-ni reached Hagaru-ri about 9:00 p.m. on 3 December. We arrived with 1,500 dead and wounded. It had taken 59 hours for the lead column to travel the 14 miles from Yudam-ni. All who could walk – including the wounded – were formed up. To the cadence of feet crunching in the snow, we marched into Hagaru-ri singing the Marine Corps Hymn! The battalion surgeon shouted, “Look at those bastards, those Magnificent Bastards!” They were as glad to see us as we were to be there. By joining forces, it greatly increased our odds of survival.

On 3 December, the cooks at Hagaru-ri provided hot pancakes and hot coffee around the clock. It was practically the only real food or liquid we would have for thirteen days until we reached the seaport of Hungnam.

We found a supply of 155mm ammunition which we fired with our remaining guns until it was depleted, and we became infantry again. A request for mortar ammunition was made using the code word “TOOTSIEROLL.” The Army Air Force in Japan did not realize that it was a code. Instead of mortar ammunition, C-119’s flew low overhead and showered us with Tootsie Rolls! These Tootsie Rolls, which we thawed in our mouths, became the nourishment that saved our lives! Tootsie Rolls are to be found everywhere at our reunions. A representative of the company attends most of them.

Our engineers had chiseled a rough airstrip on the frozen ground at Hagaru-ri, and this was used to evacuate more than 6,000 wounded and fly in more than 500 replacements. With reinforcements flown in, I once again became an infantryman. Our next task was to fight our way to Koto-ri, some ten miles distant. Once we reached Koto-ri, we would have to fight another thirty-seven miles to Chinhung-ni, which was held by the Third Army Division to protect the port of Hungnam. There the navy had assembled a fleet of transports waiting to evacuate us, should we make it.

During the ten miles to Koto-ri, we had to fight through eleven roadblocks. I remember passing through Hell Fire Valley where Task Force Drysdale had been ambushed. It was in the middle of the night with a bright moon and large snowflakes floating gently down in total silence. Burned tanks, trucks, and other vehicles were piled high in a draw and covered with snow, creating a ghostly scene. We loaded the dead onto trucks and continued to fight our way through nine more roadblocks to Koto-ri. The lead elements reached Koto-ri on 9 December. Our chance of survival increased with each step.

What is now known as “The Most Epic Battle in Marine Corps History” began on the night of 27 November 1950 when Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) attacked all UN Forces in North Korea. We now faced a new war against a new and powerful enemy. Ten Chinese divisions surrounded and were ready to destroy the isolated outposts of Marines one by one. Our survival, as well as most UN forces in North Korea, was suddenly in jeopardy!

I was with the Marines at Yudam-ni, which was the furthest the Marines advanced into North Korea, when the Chinese suddenly appeared and surrounded all UN Forces in North Korea. Their orders were to annihilate the 1st Marine Division to the last man. They were seasoned combat troops, having fought the Japanese, as well as the Nationalists in the recent civil war.

Around 10:00 p.m. on 27 November, we saw flares and heard bugles and whistles. The Marines inflicted heavy casualties upon the waves of attacking Chinese, but Marine casualties were also great – more than 500 wounded were brought into our area the first night. We cared for some of them in tents, but others had to stay outside in sleeping bags where the temperature had dropped to 30 degrees below zero. Blood froze, which prevented many wounded Marines from bleeding to death, but blood plasma also froze. Corpsmen thawed morphine vials in their mouth. The Chinese attack was such a surprise that many Marines were bayoneted in their sleeping bags – moisture from their breath had frozen the zippers.

The attack was stopped just 200 yards from our artillery battery. We loaded several hundred wounded and dead onto vehicles and formed a convoy. I became a “ridge runner” walking the ridge to guard the convoy from an enemy flank attack. I picked up a Garand M-1 rifle, a reliable weapon which had been left by a wounded or dead Marine. How I must have looked wearing a cartridge belt with ten clips (eight bullets each) of ammunition around my waist and a bandolier with another ten clips over each shoulder, plus four hand grenades dangling from my chest! That alone should have scared the bravest Chinese soldier.

The Chinese failed to destroy the Marines on the west side of the reservoir as the Chinese general had planned. Their intelligence forces were not aware that the 5th Regiment had joined forces with those on the west side and were thus a greater force than the general had expected.

Artillery to Infantry

Instead of being home for Christmas, as General McArthur had promised, our survival – as well as that of most UN forces in North Korea – was suddenly in jeopardy. We were at risk of annihilation! An order was issued for all units to provide men for the infantry. The even numbered gun crews from Love Battery were selected. I was on gun number one. We found we could only man four of the six guns.

The “cannon-infantry” men were sent to the top of Hill 1542, which commanded the road below, the road that was vital to our escape. The lieutenant in charge remained in a warm tent at the base of the hill, leaving Sgt. Jim Johnson to command the unit designated as Jig Company 7th Marine Regiment.

Around 4:30 a.m., a large force of Chinese wearing U.S. Marine parkas attacked Jig Company. The Marines held their fire, not knowing who they were until they were upon them. That was when they discovered that their carbines would not fire in such cold weather. Several Marines were killed and the unit was in danger of being overrun when Sgt. Johnson, realizing the situation was hopeless, gathered all the grenades. While he held off the attacking enemy, he ordered a withdrawal of the remaining force. He was last seen alive in hand to hand combat. For his actions in saving so many lives, he received the Medal of Honor posthumously.

Our howitzers had to fire at a very high angle due to the short distance to the target. It was probably the highest angle ever fired by a 155mm howitzer. Several howitzers were damaged when in recoil they hit the frozen ground. We found it necessary to somehow dig or blast a “recoil pit.” It was probably the first time in Marine Corps history.

We fired on villages to the north occupied by the Chinese, but with no visibility, results were unknown. After we fired the last of our ammunition, we hitched the guns to the prime movers and became infantrymen.

Frozen

Twice I encountered a group of Chinese soldiers barely visible in the falling snow. I fired a clip (eight bullets) at them, but I was unable to keep them in sight, and they did not return fire. It was difficult walking the steep banks in the deep snow and my frozen feet were in extreme pain. Our boots were made of rubber, totally inadequate for such cold. They had half-inch-thick felt insoles to absorb perspiration. The insoles froze, and it was like walking barefoot on ice. Whenever possible, I tried to dry out the felt insoles, each time cracking ice or frozen perspiration from my toes. Our breath and tears froze. All who served at Chosin suffer from long term cold injury, including nerve damage and pain that intensifies with age.

Toktong Pass

Seven miles south of Yudam-ni was Toktong, a vital mountain pass which was held by Fox Company of the 7th Marines. It was commonly called “Fox Hill.” Surrounded, the only way Fox Company could be supplied was by air drop. Several times the parachutes drifted into Chinese territory. Fortunately, one battery of 105mm howitzers in Hagaru-ri could support them by firing maximum range.

Fox Company was unable to treat or evacuate their wounded. Since they could not dig foxholes in the frozen ground, they stacked dead Chinese like sandbags for protection. They decimated almost an entire Chinese division while holding the pass, until a force from Yudam-ni was able to reach them. Guided only by the stars at night and a compass during the day, a relief column led by Lt. Col. Ray Davis marched through waist-deep snow around the back side of the mountains until they reached Fox Hill. The road from Yudam-ni was then cleared by taking the hills on each side of the road.

With the road cleared, our convoy left Yudam-ni on 1 December and arrived at the pass a few hours later. We loaded the wounded and dead aboard trucks. It was one of the most difficult things I have ever done. The dead bodies were frozen in the position in which they died. Reluctantly, I gave my sleeping bag to a wounded Marine. There would be little chance for me to sleep anyway until we reached Hagaru-ri. We would fall asleep walking and wander off the road, or doze off in the middle of a sentence while talking. I would sit on my helmet, which had a round bottom, and as I fell asleep I would fall over and wake up. While asleep, I would feel warm and totally at peace; I believe that is how it feels just before you freeze to death.

On to Hagaru-ri

From Toktong Pass it was about eight miles to Hagaru-ri at the base of the reservoir. Five inches of new snow had fallen. The Chinese had destroyed all the bridges and blown out sections of the mountain road. The narrow road was a sheet of ice. Again, I became a ridge runner to protect the convoy from ambush. There were times that I could not walk the flanks due to the terrain and had to walk the road. I remember a Chinese heavy machine gun firing at me from across a valley. I could see that his bullets were hitting the snow bank over my head, but I was too exhausted to care, so I continued to walk while he kept firing, never realizing that his sights were off.

We lost one truck when it slipped off the icy road and down a steep hill side. We had to burn it to destroy what we could not salvage. One truck loaded with wounded that was pulling a trailer loaded with wounded slid over the side and down a steep embankment in the middle of the night killing several of the wounded. They had to be brought back up to the road and placed wherever there was a place in the convoy, such as on a hood or fender or even on top of other wounded.

As we moved, I found myself near the end of the column. This is where the howitzers were – to prevent them from blocking the road if they became disabled. About midnight, just short of Hagaru-ri, some of the prime movers (tractors) pulling our guns ran out of diesel fuel, creating a gap in the column and the opportunity the Chinese had been waiting for.

First, they knocked out a tank from Hagaru-ri that had been sent to assist us at a bridge over an inlet, effectively blocking the road. The tank was burning, and ammunition was exploding. The flames cast a glow to the advantage of the Chinese. They went after the howitzers, firing at the tractor drivers and into the radiators. I was blinded by the flash of my first shot and I could only fire into the darkness where I thought the Chinese were. We killed several Chinese, but we also suffered casualties. I left our tractor driver for dead in the roadside ditch, but he showed up later in not much of a forgiving mood. I still bear a feeling of guilt for this.

We had to abandon nine guns by pushing them off the road. Then to reach Hagaru-ri, we had to run past the exploding tank. At first light, the British 41 Commando tried to retrieve the howitzers, but the Chinese drove them back. Army fighter planes attempted to drop napalm on them but missed. The Chinese now had nine of our eighteen 155mm howitzers, including my gun and all of my possessions.

Going back to the evening of 27 November, the Army 31st Regimental Combat Team relieved the 5th Marines on the east side of the reservoir, which allowed the 5th Marines to join the 7th Marines on the west side of the reservoir. A large force of Chinese attacked the Army units on the east, and for several days the Army engaged the Chinese force that would have otherwise been available to attack Hagaru-ri. In my opinion, this effectively kept the Chinese from seizing Hagaru-ri before the Marines from Yudam-ni were able to get there, and the Chinese were prevented from achieving their strategic objective to trap and annihilate all UN forces at Chosin.

Task Force Faith

The Army was ordered to form a force to fight their way to Hagaru-ri. Known as Task Force Faith, after Lt. Col. Don Faith, they loaded their wounded aboard trucks and decided to run the road blocks to reach Hagaru-ri. The lead truck was knocked out at the first road block, effectively blocking the road. The trucks that followed, which were carrying the wounded, attempted to go around it but were stopped. The Chinese converged on the trucks, machine gunned them, and set them on fire.

An attempt by Army tanks from Hagaru-ri to reinforce Task Force Faith had been turned back, and the Army unit that Task Force Faith was expecting to meet up with at Hudong-ni was not there. It had been withdrawn earlier to help reinforce Hagaru-ri.

Task Force Faith was effectively defeated, and each man was on his own. They were forced to abandon everything, including quad 50 caliber machine guns and twin 40mm anti-aircraft guns that had been extremely effective against the Chinese. About 400 able-bodied men and 1,500 wounded drifted into Hagaru-ri a few at a time. They either walked through the hills in waist-deep snow or over the frozen reservoir. Lt. Col. Faith was not among them.

Task Force Drysdale

Hagaru-ri was badly in need of reinforcements to hold until the Marines from Yudam-ni arrived. In a desperate attempt to help, a task force from Koto-ri, some ten miles south, was ordered to attack north to Hagaru-ri. Named Task Force Drysdale after the British commander of the Royal Marines, it was made up of the British 41 Commando and elements of the 1st Marine Regiment. They managed to reach a point half way between Hagaru-ri and Koto-ri where – at what was to become known as Hell Fire Valley – the Chinese ambushed the force, killing and wounding a large number. Numerous vehicles, including tanks, were destroyed and blocked the road, most in a jumbled heap. Some Marines ran out of ammunition, and the Chinese took them prisoner. Drysdale radioed General Smith at Hagaru-ri of the situation. He asked if he should turn back or try to get through with the remaining force. General Smith’s orders were to continue the attack “at all costs,” which they did. Of the 900 who left Koto-ri, 400 made it to Hagaru-ri.

Attack on Hagaru-ri

The Chinese had broken thru the defense perimeter of Hagaru-ri the night before we arrived from Yudam-ni, but they were driven back by a counterattack. Hagaru-ri was in danger of being overrun a second time, which would have proved fatal. That’s when 2nd Lieutenant Dick Carey sent out two South Koreans in Chinese uniforms to mingle with the Chinese in an attempt to find out where and when the next attack on Hagaru-ri would take place. They returned with the information, and the perimeter was reinforced. The Chinese attack came at the place they had determined, but it was off by one hour. Lt. Carey took a lot of kidding for failing to find out if the Chinese were on daylight savings time.

Hagaru-ri road block

In the attack, the Chinese suffered heavy casualties and were unable to penetrate the reinforced defense. The intelligence probably saved Hagaru-ri and the lives of thousands of Marines. However, Hagaru-ri would still be extremely vulnerable until the Marines from Yudam-ni arrived.

Magnificent Bastards

The first contingent of Marines from Yudam-ni reached Hagaru-ri about 9:00 p.m. on 3 December. We arrived with 1,500 dead and wounded. It had taken 59 hours for the lead column to travel the 14 miles from Yudam-ni. All who could walk – including the wounded – were formed up. To the cadence of feet crunching in the snow, we marched into Hagaru-ri singing the Marine Corps Hymn! The battalion surgeon shouted, “Look at those bastards, those Magnificent Bastards!” They were as glad to see us as we were to be there. By joining forces, it greatly increased our odds of survival.

On 3 December, the cooks at Hagaru-ri provided hot pancakes and hot coffee around the clock. It was practically the only real food or liquid we would have for thirteen days until we reached the seaport of Hungnam.

We found a supply of 155mm ammunition which we fired with our remaining guns until it was depleted, and we became infantry again. A request for mortar ammunition was made using the code word “TOOTSIEROLL.” The Army Air Force in Japan did not realize that it was a code. Instead of mortar ammunition, C-119’s flew low overhead and showered us with Tootsie Rolls! These Tootsie Rolls, which we thawed in our mouths, became the nourishment that saved our lives! Tootsie Rolls are to be found everywhere at our reunions. A representative of the company attends most of them.

Our engineers had chiseled a rough airstrip on the frozen ground at Hagaru-ri, and this was used to evacuate more than 6,000 wounded and fly in more than 500 replacements. With reinforcements flown in, I once again became an infantryman. Our next task was to fight our way to Koto-ri, some ten miles distant. Once we reached Koto-ri, we would have to fight another thirty-seven miles to Chinhung-ni, which was held by the Third Army Division to protect the port of Hungnam. There the navy had assembled a fleet of transports waiting to evacuate us, should we make it.

During the ten miles to Koto-ri, we had to fight through eleven roadblocks. I remember passing through Hell Fire Valley where Task Force Drysdale had been ambushed. It was in the middle of the night with a bright moon and large snowflakes floating gently down in total silence. Burned tanks, trucks, and other vehicles were piled high in a draw and covered with snow, creating a ghostly scene. We loaded the dead onto trucks and continued to fight our way through nine more roadblocks to Koto-ri. The lead elements reached Koto-ri on 9 December. Our chance of survival increased with each step.

☆ Chapter One: Pearl Harbor to Camp Tarawa

☆ Chapter Two: Saipan

☆ Chapter Three: Okinawa

☆ Chapter Four: The End of WWII

☆ Chapter Five: Korea