Stories by Others About the Sixth Division, the Marines, and World War II

My Grandpa's War

by John R. Legg, grandson of Willard Legg (22nd Mar-3-L)

I laid awake in the spare bedroom of my grandparents’ house, staring at the dark ceiling above my head. In the next room over, my Grandpa Willard abruptly woke up with a ghastly-sounding scream. He was laying in a hospital bed, ill, nearly blind, and missing limbs from his prolonged fight with diabetes. The rattling of the bed rails echoed down the hallway. Without hesitation, my grandma rushed into his room and calmed him down. I could tell it wasn’t the phantom limb pain causing him issues that night. What-ever woke him up was deep in his soul. I closed my eyes and attempted to fall back asleep as I heard Grandpa’s muffled weeping coming through the walls next to me.

The following morning, I walked past the bedroom door. Grandpa called out my name as I walked by and asked me to sit beside him. He asked, “Did you hear me last night, John?” A true sadness washed over his face when I said yes. “I think it’s time for me to tell you about what makes me so scared at night.” I pulled up a chair beside his bed, and Grandpa Willard began to tell me about his experiences fighting on Okinawa —something he rarely spoke of, even with his wife and children. That morning, as I held his hand, I learned of his bravery, his dedication, and his nightmares. I vividly remember the first words of his story: “It was like Hell on Earth.”

Tears rushed down his face as his mind transported him back to 1945. Evocative memories came to life, and he recounted stories with his eyes closed and his fists clenched. I could tell he had been holding on to these memories for a lifetime.

Before I share his stories, I would like to introduce you to my Grandpa. Born in 1925 and the oldest of eleven children, Willard Darrell Legg grew up in Fola, a small community in Clay County, West Virginia. Like other places around the nation, Clay County sent many young men off to World War II. From my family, Charles (Army), Clyde (Navy), and Henry (Navy), to name a few, participated in some of the bloodiest battles of the war. Willard enlisted in the USMC as a private in 1943 at eighteen years old. By September 1944, he and his fellow Marines of the 22nd Regiment had moved to Guadalcanal, where his unit joined the newly formed 6th Marine Division.

On April 1, 1945, Willard landed on the shores of Okinawa. Over the next month, he and his 22nd Marines trekked through the muddy countryside of the island.

Sometime in late April, he and his unit bedded down for the night in a rice patty field during their advance toward the Shuri Line. Grandpa told me that those moments are what haunted him the most. “You never knew when they would attack,” he told me, “One moment, it was quiet, and the next, an entire Japanese company would charge at our position, or artillery shells would explode around us.” Willard and one of his fellow Marines hunkered down in a fighting hole. His buddy told him to get some rest and that he would be on watch for the next few hours. As they settled in the fighting hole, both Marines dozed off out of sheer exhaustion. A short time later, Willard’s intuition woke him up. He never understood what caught his attention but was glad something woke him up.

A collage of objects that memorialize Willard D. Legg, including

postcard images from Okinawa, the Sixth Marine Division patch,

a portrait of Willard taken in 1943, and his Purple Heart

As he opened his eyes, Willard noticed a short Japanese soldier diving down at him. The Japanese soldier had killed his comrade. Screaming profusely, the Japanese soldier had his sharp bayonet in his hand and was ready to pierce Willard in the chest. Luckily, Willard evaded the stabbing and began to fight with the soldier in the fighting hole. He recounted the trauma of this moment and said he exited his position and ran back further behind American lines. He screamed as loud as he could, “This is Legg; get number two, SHOOT THE SECOND MAN, SHOOT THE SECOND MAN!” A few moments later, a Marine shot the Japanese soldier, and Willard could stop running. He was out of breath, shaking from adrenaline and fear. Willard never blamed his mate, who fell asleep beside him; he was just glad he made it out alive.

Willard returned to his fighting hole, with several traumatic moments through the coming days and weeks, especially a night when he killed a Japanese officer during a full-on bonzai charge. Memories of the battlefield carnage also remained deep in his conscious: seeing Okinawan civilians hurl themselves off cliffs to escape the terror induced by the Japanese soldiers, friends dying, loud concussive explosions, bullets whizzing by his helmet.

Willard continued to hold my hand as he recounted his traumatic memories from the war. With each squeeze, I felt more and more attached to his experiences on Okinawa.

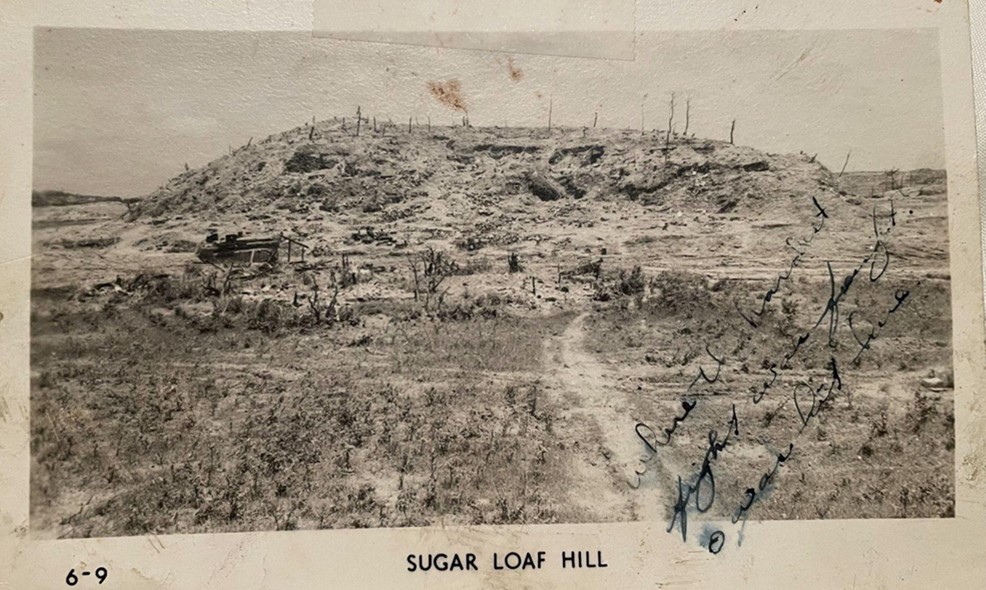

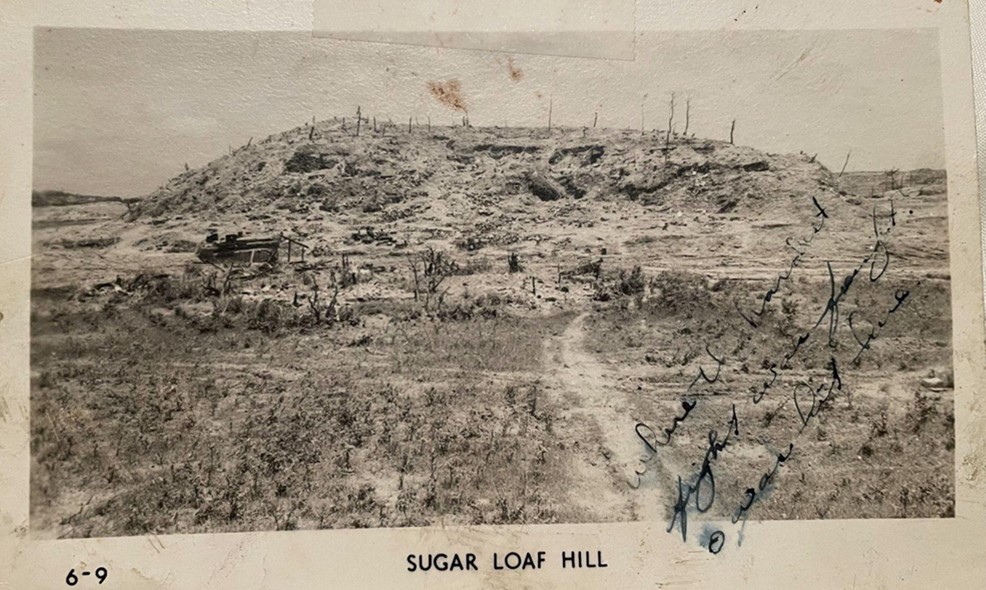

Near the end of the conversation, Willard asked me to look in a box next to his bedstand and told me that he was giving me its contents. I opened the container to find several postcards, a uniform patch, a portrait of him taken in 1943, and a maroon-colored box filled with his Purple Heart medal. He asked me to look through the postcards and find one with the name “Sugar Loaf Hill” on it. I found the picture and saw a barren hill in the middle of the frame. An “x” was hand-drawn on the image with an annotation nearby, which read, “Where the hardest fight was fought. I was hit here.” Grandpa pointed to the “x” and said, “This is where I was wounded.” I listened intently, absorbing every detail. He told me about Sugar Loaf Hill and how the Marines sent several advances toward the heavily defended Japanese position. I have learned since that day that the struggle to control this small position was one of the costliest for the Marines, especially those of the 6th Marine Division.

On May 16, 1945, Willard and his buddies in the 22nd Marines charged up Sugar Loaf Hill. A Japanese grenade exploded behind him and sent shrapnel into his back. He fell, finding respite from the carnage happening in front of him. A Navy Corpsman rushed and mended his wounds, and stretchers took him back back toward safety once the fighting calmed down.

Willard’s postcard of Sugar Loaf Hill with the line “Where the hardest

fight was fought. I was hit here.”

After Okinawa, Willard recovered from his wounds on Guam, ironically in the same hospital where his younger brother, Clyde, recovered from a bout of malaria. He returned to duty and prepared for the invasion of Honshū. After the Japanese surrender, Willard spent time as a guard in Tsingtao, China between 1945 and 1946. I never heard much about his time there. My Uncle Dave, however, told me that “their basic job was to repatriate Japanese troops” that surrendered in China at the end of the war. “Some of his company was loaned out to the army briefly in Nagasaki,” my Uncle Dave continued to tell me, and “Dad described it as ‘clean up,’ but he wouldn’t say anything about it.”

Willard returned to West Virginia after the war and worked in the coal mines. He married my grandma Ethel, or Mickey as we called her, and they had five sons.

Willard was a lifelong advocate for those suffering from black lung disease, even though he only worked in the mines for a few years. During a strike, a union buster shot one of the miners, quickly inspiring Willard to leave West Virginia and search for a new life in Michigan. He worked in the automotive industry for many years before becoming a Baptist preacher.

Willard passed away in 2004, just two years after he shared his war stories with me.

Grandpa brought back war trophies that he kept hidden for many years. My dad, as a child, saw a sword and a Japanese flag in the storage space of the Fola, West Virginia home in the 1950s. By then, the flag had started to deteriorate from dry rot. Grandpa passed the sword to my uncle, who passed it on to his son, where it remains in his collection today.

Grandpa also brought home things from the war he couldn’t share with those he loved. His buddies died next to him in the fighting holes, on Sugar Loaf Hill, and all the way until the Japanese surrendered, yet he escaped Okinawa with only a few wounds that eventually healed. In addition to the PTSD from horrifying combat, Willard also suffered from survivor’s guilt.

I am thankful Grandpa Willard gave me the material objects that memorialized his time on Okinawa. Yet, it was his stories that have stuck with me all of these years. Listening to stories allows us to understand personal experiences from the past. Typical history books focus on the published record: newspaper reports, governmental documents, letters, photos, and maps, to name a few. However, individual stories garner a deeper understanding of how people experienced certain events or lived through challenging times.

Listening to Grandpa Willard’s stories inspired me to become a historian, where I routinely center these perspectives in my work. While I am not a World War II historian (I write on Native American history during the Civil War era), what I learned from my Grandpa and the time I spent reliving his experiences influences my work. Scholars studying the Civil War have generally ignored or overlooked Native voices and perspectives.

Oral history and storytelling reframe certain events and paint a more vivid portrait of our collective past. Listening to my Grandpa’s storytelling fascinated me, and his personal experiences influenced my understanding of the past. Stories from the 6th Marine Division demonstrate how the fight did not end in 1945 but continued throughout the rest of their lives.

I am not sure why he wanted to share his stories with me. I was only twelve years old, and I want to believe that he saw a passion inside me that would carry forward and honor his place in history. He knew that I’d forever remember his legacy after he passed on. This experience taught me that history needs empathy.

As I left my Grandpa’s bedside, holding his Purple Heart and the weight of his stories, I realized that his bravery and sacrifice would be forever etched in my memory.

The following morning, I walked past the bedroom door. Grandpa called out my name as I walked by and asked me to sit beside him. He asked, “Did you hear me last night, John?” A true sadness washed over his face when I said yes. “I think it’s time for me to tell you about what makes me so scared at night.” I pulled up a chair beside his bed, and Grandpa Willard began to tell me about his experiences fighting on Okinawa —something he rarely spoke of, even with his wife and children. That morning, as I held his hand, I learned of his bravery, his dedication, and his nightmares. I vividly remember the first words of his story: “It was like Hell on Earth.”

Tears rushed down his face as his mind transported him back to 1945. Evocative memories came to life, and he recounted stories with his eyes closed and his fists clenched. I could tell he had been holding on to these memories for a lifetime.

Before I share his stories, I would like to introduce you to my Grandpa. Born in 1925 and the oldest of eleven children, Willard Darrell Legg grew up in Fola, a small community in Clay County, West Virginia. Like other places around the nation, Clay County sent many young men off to World War II. From my family, Charles (Army), Clyde (Navy), and Henry (Navy), to name a few, participated in some of the bloodiest battles of the war. Willard enlisted in the USMC as a private in 1943 at eighteen years old. By September 1944, he and his fellow Marines of the 22nd Regiment had moved to Guadalcanal, where his unit joined the newly formed 6th Marine Division.

On April 1, 1945, Willard landed on the shores of Okinawa. Over the next month, he and his 22nd Marines trekked through the muddy countryside of the island.

Sometime in late April, he and his unit bedded down for the night in a rice patty field during their advance toward the Shuri Line. Grandpa told me that those moments are what haunted him the most. “You never knew when they would attack,” he told me, “One moment, it was quiet, and the next, an entire Japanese company would charge at our position, or artillery shells would explode around us.” Willard and one of his fellow Marines hunkered down in a fighting hole. His buddy told him to get some rest and that he would be on watch for the next few hours. As they settled in the fighting hole, both Marines dozed off out of sheer exhaustion. A short time later, Willard’s intuition woke him up. He never understood what caught his attention but was glad something woke him up.

A collage of objects that memorialize Willard D. Legg, including

postcard images from Okinawa, the Sixth Marine Division patch,

a portrait of Willard taken in 1943, and his Purple Heart

As he opened his eyes, Willard noticed a short Japanese soldier diving down at him. The Japanese soldier had killed his comrade. Screaming profusely, the Japanese soldier had his sharp bayonet in his hand and was ready to pierce Willard in the chest. Luckily, Willard evaded the stabbing and began to fight with the soldier in the fighting hole. He recounted the trauma of this moment and said he exited his position and ran back further behind American lines. He screamed as loud as he could, “This is Legg; get number two, SHOOT THE SECOND MAN, SHOOT THE SECOND MAN!” A few moments later, a Marine shot the Japanese soldier, and Willard could stop running. He was out of breath, shaking from adrenaline and fear. Willard never blamed his mate, who fell asleep beside him; he was just glad he made it out alive.

Willard returned to his fighting hole, with several traumatic moments through the coming days and weeks, especially a night when he killed a Japanese officer during a full-on bonzai charge. Memories of the battlefield carnage also remained deep in his conscious: seeing Okinawan civilians hurl themselves off cliffs to escape the terror induced by the Japanese soldiers, friends dying, loud concussive explosions, bullets whizzing by his helmet.

Willard continued to hold my hand as he recounted his traumatic memories from the war. With each squeeze, I felt more and more attached to his experiences on Okinawa.

Near the end of the conversation, Willard asked me to look in a box next to his bedstand and told me that he was giving me its contents. I opened the container to find several postcards, a uniform patch, a portrait of him taken in 1943, and a maroon-colored box filled with his Purple Heart medal. He asked me to look through the postcards and find one with the name “Sugar Loaf Hill” on it. I found the picture and saw a barren hill in the middle of the frame. An “x” was hand-drawn on the image with an annotation nearby, which read, “Where the hardest fight was fought. I was hit here.” Grandpa pointed to the “x” and said, “This is where I was wounded.” I listened intently, absorbing every detail. He told me about Sugar Loaf Hill and how the Marines sent several advances toward the heavily defended Japanese position. I have learned since that day that the struggle to control this small position was one of the costliest for the Marines, especially those of the 6th Marine Division.

On May 16, 1945, Willard and his buddies in the 22nd Marines charged up Sugar Loaf Hill. A Japanese grenade exploded behind him and sent shrapnel into his back. He fell, finding respite from the carnage happening in front of him. A Navy Corpsman rushed and mended his wounds, and stretchers took him back back toward safety once the fighting calmed down.

Willard’s postcard of Sugar Loaf Hill with the line “Where the hardest

fight was fought. I was hit here.”

After Okinawa, Willard recovered from his wounds on Guam, ironically in the same hospital where his younger brother, Clyde, recovered from a bout of malaria. He returned to duty and prepared for the invasion of Honshū. After the Japanese surrender, Willard spent time as a guard in Tsingtao, China between 1945 and 1946. I never heard much about his time there. My Uncle Dave, however, told me that “their basic job was to repatriate Japanese troops” that surrendered in China at the end of the war. “Some of his company was loaned out to the army briefly in Nagasaki,” my Uncle Dave continued to tell me, and “Dad described it as ‘clean up,’ but he wouldn’t say anything about it.”

Willard returned to West Virginia after the war and worked in the coal mines. He married my grandma Ethel, or Mickey as we called her, and they had five sons.

Willard was a lifelong advocate for those suffering from black lung disease, even though he only worked in the mines for a few years. During a strike, a union buster shot one of the miners, quickly inspiring Willard to leave West Virginia and search for a new life in Michigan. He worked in the automotive industry for many years before becoming a Baptist preacher.

Willard passed away in 2004, just two years after he shared his war stories with me.

Grandpa brought back war trophies that he kept hidden for many years. My dad, as a child, saw a sword and a Japanese flag in the storage space of the Fola, West Virginia home in the 1950s. By then, the flag had started to deteriorate from dry rot. Grandpa passed the sword to my uncle, who passed it on to his son, where it remains in his collection today.

Grandpa also brought home things from the war he couldn’t share with those he loved. His buddies died next to him in the fighting holes, on Sugar Loaf Hill, and all the way until the Japanese surrendered, yet he escaped Okinawa with only a few wounds that eventually healed. In addition to the PTSD from horrifying combat, Willard also suffered from survivor’s guilt.

I am thankful Grandpa Willard gave me the material objects that memorialized his time on Okinawa. Yet, it was his stories that have stuck with me all of these years. Listening to stories allows us to understand personal experiences from the past. Typical history books focus on the published record: newspaper reports, governmental documents, letters, photos, and maps, to name a few. However, individual stories garner a deeper understanding of how people experienced certain events or lived through challenging times.

Listening to Grandpa Willard’s stories inspired me to become a historian, where I routinely center these perspectives in my work. While I am not a World War II historian (I write on Native American history during the Civil War era), what I learned from my Grandpa and the time I spent reliving his experiences influences my work. Scholars studying the Civil War have generally ignored or overlooked Native voices and perspectives.

Oral history and storytelling reframe certain events and paint a more vivid portrait of our collective past. Listening to my Grandpa’s storytelling fascinated me, and his personal experiences influenced my understanding of the past. Stories from the 6th Marine Division demonstrate how the fight did not end in 1945 but continued throughout the rest of their lives.

I am not sure why he wanted to share his stories with me. I was only twelve years old, and I want to believe that he saw a passion inside me that would carry forward and honor his place in history. He knew that I’d forever remember his legacy after he passed on. This experience taught me that history needs empathy.

As I left my Grandpa’s bedside, holding his Purple Heart and the weight of his stories, I realized that his bravery and sacrifice would be forever etched in my memory.