Stories by Sixth Division Marines

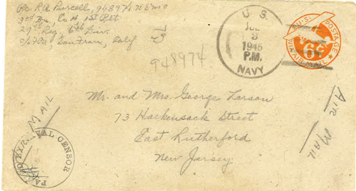

35-Year-Old Robert Purcell Writes to Family Friends from Okinawa

|

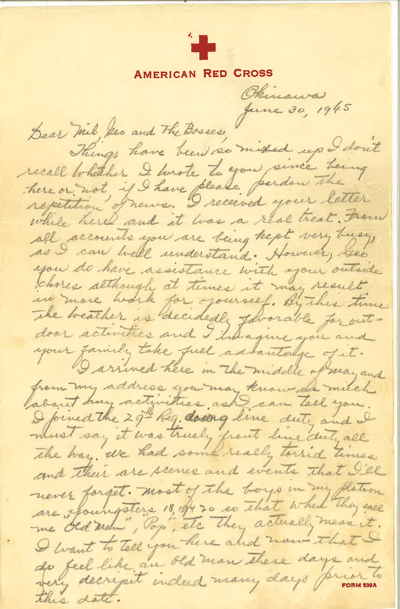

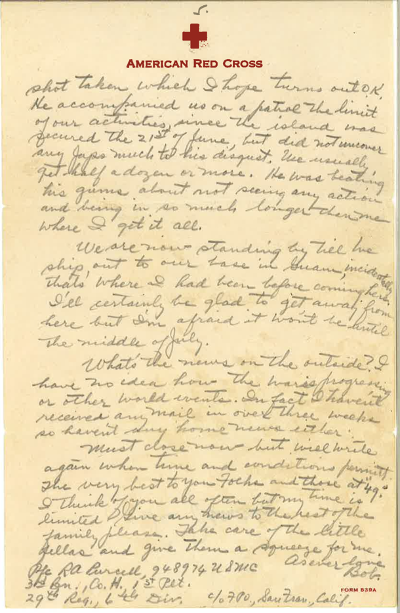

Okinawa June 30, 1945 Dear Mil, Geo and The Bosses, Things have been so mixed up I don’t recall whether I wrote to you since being here or not; if I have please pardon the repetition of news. I received your letter while here and it was a real treat. From all accounts you are being kept very busy, as I can well understand. However, Geo you do have assistance with your outside chores although at times it may result in more work for yourself. By this time the weather is decidedly favorable for outdoor activities and I imagine you and your family take full advantage of it. I arrived here in the middle of May and from my address you may know as much about my activities as I can tell you. I joined the 29th Reg. doing line duty and I must say it was truly front line duty all the way. We had some torrid times and there are scenes and events that I’ll never forget. Most of the boys in my platoon are youngsters 18, 19 and 20 so that when they call me “Old Man,” “Pop,” etc, they actually mean it. I want to tell you here and now that I do feel like an old man these days and very decrepit indeed many days prior to this date. Our platoon started with a complement of 38 men and finished with a total of six. The casualty rate was around 130%. Words seem so inadequate in describing the situation here and I don’t believe anyone can realize what it was like without being a witness or participant. It’s indescribable the lengths the Japs went to in fortifying the island. As you probably know, the island is a series of mountains and to add to it a goodly number of hills were manmade. Each and every mound of dirt was a series of caves and the larger hills were so lined with caves that they resembled our three storied structures. They’d have a shaft in the middle going to the top with tunnels leading out in every direction all connecting and going entirely thru the hill. The upright shafts, of course, had ladders while many of the caves had railroad ties for artillery, etc. The openings of some caves had steel doors or they would be located further back in the cave. The Nips would pop up in one cave, fire (mortar, artillery, rifle and machine gun fire), disappear and come out at another opening. I must say if you hear anyone state that the Japs can’t shoot, tell him he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. Geo, they can by all means and their snipers are deadly. Their equipment is excellent and plentiful. I feel very lucky to be alive and most fortunate indeed not to have been wounded. I’ve been pinned down many times by sniper and automatic rifle fire and mortar fire with many around me being killed and wounded, and I must say it’s been wicked. We started our campaign just outside the city of Naha and for 16 days it rained, sometimes night and day. We were wet most of the time, our feet all the time. At nights we’d sit in our foxholes with mud and water well above our ankles. We had two-man foxholes because someone had to keep awake. The Japs would try to infiltrate at night and grenades were thrown aplenty. There are a couple of good army Reg. here, but all in all the Army certainly fouled up this operation. After completing our objective, we were recalled twice to assist the Army and while on line with them they pulled many a boner. The 27th Reg., a NY State Guard outfit, made a terrible reputation for themselves – they were absolutely lousy (pardon my expression). To add to our discomfort, we’ve been plagued with flies, mosquitos and fleas in ever increasing numbers. I never in all my life saw so many flies; they cover a man’s back so you can’t see anything but an ever-moving mass of black. The weather now is torrid, the sun being a scorcher. The odors here of course have been awful because of the dead and the living quarters of the people. You can smell a Nip even when he’s alive which was a help at night. The stench in the city of Naha was terrific. There is one thing I must hand these people which is a constant cause of wonder to me, that is the pain they endure without a whimper. I’ve seen them as young as 5 years of age and old people with gaping wounds in all parts of their body walking along, receive treatment and continue to walk along without a whimper from them. As you probably know, Howard [Robert’s brother] is here also and although I wasn’t able to locate him, he did drop in on me the other day. He was a sorry but most welcome sight to me. He was covered in dust from head to foot, needed a shave, etc. We had a snap shot taken which I hope turns out OK. He accompanied us on a patrol, the limit of our activities since the island was secured the 21st of June, but did not uncover any Japs much to his disgust. We usually get half a dozen or more. He was beating his gums about not seeing any action and being in so much longer than me where I get it all. We are now standing by till we ship out to our base in Guam, incidentally that’s where I had been before coming here. I’ll certainly be glad to get away from here but I’m afraid it won’t be until the middle of July. What’s the news on the outside? I have no idea how the war is progressing or other world events. In fact, I haven’t received any mail in over three weeks so haven’t any home news either. Must close now but will write again when time and conditions permit. The very best to you folks and those at “49.” I think of you all the time but my time is limited. Give any news to the rest of the family please. Take care of the little fellas and give them a squeeze for me. As ever, love Bob PFC R.A. Purcell 948974, USMC 3rd Bn, Co. H, 1st Plt. 29th Reg., 6th Div. c/o FPO, San Fran. Calif. |

Bart Purcell Remembers His Father: “Don’t Drip Blood on the Rug.”

My dad died on January 3, 1983. He was 73. At his wake, a family friend handed me four envelopes, each containing a letter written by my dad when he was in the military. The fourth and final letter [see page 4] was written from Okinawa on June 30, 1945, about a week after United States forces secured the island.

Because I was born 11 years after World War II ended, all I knew about my dad’s military service was that he was a Marine, he was a riflery instructor at Parris Island, and he fought on Okinawa. Most of this I learned from others, because my dad never spoke of Okinawa. Not that the subject was forbidden; he would answer any question I asked, but he did not elaborate. His answers were short and to the point. My 10-year-old self might ask, “Dad, did you ever kill any of them?” And he’d say something like, “Hard to know. I was too busy trying to stay alive.”

My dad was three years old when the Titanic sank in 1912. When he enlisted in the Marines in 1944, he was already 35 years old. He was in a difficult marriage, he had three young children, and he worked for an insurance company in New York City. The lens through which my father viewed the horrors of war was not that of a vulnerable young man eager to make his mark on the world, but that of a man already toughened by life’s difficulties.

A few years after the war, my dad got divorced. He met my mother and they married in 1952. I was born in 1956.

My cousin Beth (daughter of my dad’s brother Howard, also a Marine on Okinawa) encapsulated what it was like to grow up as a Purcell. Complaining was not allowed, whining was not tolerated and – most importantly – “Don’t drip blood on the rug.” Perfect. There was a lot of love thrown in there to be sure, but it’s a fair take on things.

My dad was my moral compass. He was a man of utmost integrity. In retrospect, honesty was the driving force in his life. A college professor of mine, at the end of the last class he would ever teach, wanted to share his philosophy on how a life should be lived. He said “I live my life so that when I get up in the morning and look in the mirror, my disgust is purely aesthetic.” Although my father would never put it that eloquently, this was his philosophy too.

When I was a child and in some moral quandary, my dad would explain which was the right path and which was the wrong one and why. When I became a teenager, if I approached him similarly, he would say, “You already know the answer. You’re asking me so that I will give you ‘permission’ to do the wrong thing.” And, of course, he was right. You only get one shot at integrity.

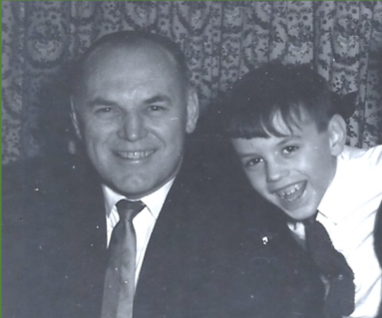

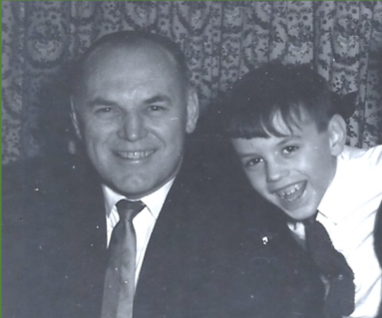

Robert Purcell and son Bart in 1964

In many ways my dad was born a Marine. He was right out of central casting. He was always fastidious, polite, reserved, and both physically and – most importantly – mentally tough.

I’d watch him shine his many pairs of dress shoes every two weeks or so. “You can be wearing a $1,000 suit and if your shoes aren’t shined, you look like hell.” He took military showers (water on, water off, soap on, rinse off), and he always dressed sharply. Whether these were the vestiges of a Marine’s life or simply his way was not really something I thought about then. It was probably a bit of both. According to friends who had known him from childhood, it was absolutely consistent with his personality.

My dad never once laid his hands on me but I do remember his eyes. If he told me to do something, it was not a suggestion. It was not a signal that we were about to enter into negotiations. “Make sure the lawn is cut before you go to baseball practice” could not be pleaded down to cutting the lawn after practice. If I started to debate, I’d get the look. It wasn’t like he was angry. He was calm. Maybe a bit too calm. But his eyes said that in no way was there going to be a compromise.

My dad was the best man I have ever known. For members of the Sixth Marine Division Association, it might be simpler to just say that my dad was the quintessential Marine. He had unquestionable and uncompromising integrity. He was physically and mentally tough. He was honorable and respectful. He was courageous and loyal. He was patriotic to a fault and was never shy about expressing his love of this country. Once a Marine, always a Marine.

Because I was born 11 years after World War II ended, all I knew about my dad’s military service was that he was a Marine, he was a riflery instructor at Parris Island, and he fought on Okinawa. Most of this I learned from others, because my dad never spoke of Okinawa. Not that the subject was forbidden; he would answer any question I asked, but he did not elaborate. His answers were short and to the point. My 10-year-old self might ask, “Dad, did you ever kill any of them?” And he’d say something like, “Hard to know. I was too busy trying to stay alive.”

My dad was three years old when the Titanic sank in 1912. When he enlisted in the Marines in 1944, he was already 35 years old. He was in a difficult marriage, he had three young children, and he worked for an insurance company in New York City. The lens through which my father viewed the horrors of war was not that of a vulnerable young man eager to make his mark on the world, but that of a man already toughened by life’s difficulties.

A few years after the war, my dad got divorced. He met my mother and they married in 1952. I was born in 1956.

My cousin Beth (daughter of my dad’s brother Howard, also a Marine on Okinawa) encapsulated what it was like to grow up as a Purcell. Complaining was not allowed, whining was not tolerated and – most importantly – “Don’t drip blood on the rug.” Perfect. There was a lot of love thrown in there to be sure, but it’s a fair take on things.

My dad was my moral compass. He was a man of utmost integrity. In retrospect, honesty was the driving force in his life. A college professor of mine, at the end of the last class he would ever teach, wanted to share his philosophy on how a life should be lived. He said “I live my life so that when I get up in the morning and look in the mirror, my disgust is purely aesthetic.” Although my father would never put it that eloquently, this was his philosophy too.

When I was a child and in some moral quandary, my dad would explain which was the right path and which was the wrong one and why. When I became a teenager, if I approached him similarly, he would say, “You already know the answer. You’re asking me so that I will give you ‘permission’ to do the wrong thing.” And, of course, he was right. You only get one shot at integrity.

Robert Purcell and son Bart in 1964

In many ways my dad was born a Marine. He was right out of central casting. He was always fastidious, polite, reserved, and both physically and – most importantly – mentally tough.

I’d watch him shine his many pairs of dress shoes every two weeks or so. “You can be wearing a $1,000 suit and if your shoes aren’t shined, you look like hell.” He took military showers (water on, water off, soap on, rinse off), and he always dressed sharply. Whether these were the vestiges of a Marine’s life or simply his way was not really something I thought about then. It was probably a bit of both. According to friends who had known him from childhood, it was absolutely consistent with his personality.

My dad never once laid his hands on me but I do remember his eyes. If he told me to do something, it was not a suggestion. It was not a signal that we were about to enter into negotiations. “Make sure the lawn is cut before you go to baseball practice” could not be pleaded down to cutting the lawn after practice. If I started to debate, I’d get the look. It wasn’t like he was angry. He was calm. Maybe a bit too calm. But his eyes said that in no way was there going to be a compromise.

My dad was the best man I have ever known. For members of the Sixth Marine Division Association, it might be simpler to just say that my dad was the quintessential Marine. He had unquestionable and uncompromising integrity. He was physically and mentally tough. He was honorable and respectful. He was courageous and loyal. He was patriotic to a fault and was never shy about expressing his love of this country. Once a Marine, always a Marine.