Russia Invades Korea

The cold war in the late 1940’s was so hot it looked as if we would go to war with Russia, and I did not want to go to war with Russia as an “Infantry Assault Demolitionist.” So I enlisted for four years as a reservist with the 14th Marine 155mm Howitzer Battalion at Dallas NAS in Grand Prairie, Texas to get my MOS (Military Occupation Specialty) changed to Artillery. We trained one or two weekends each month at the Dallas Naval Air Station.

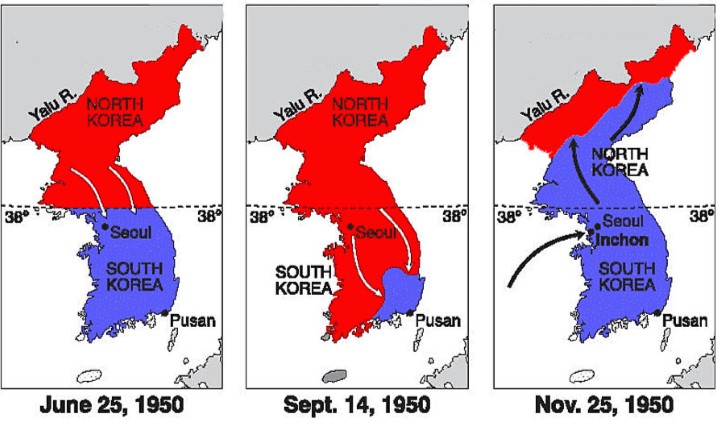

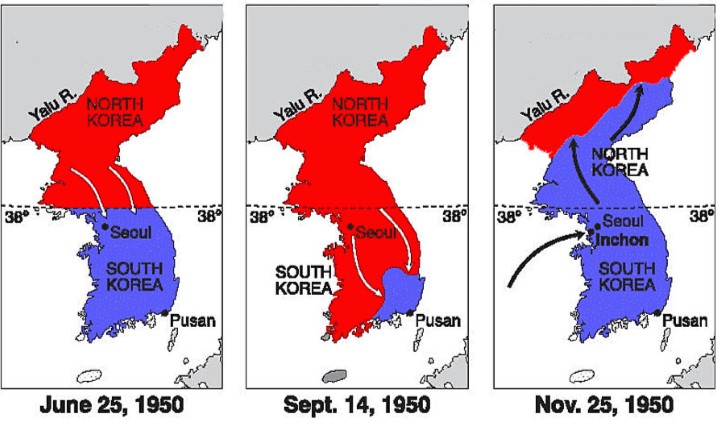

Korea had been divided after World War II. North of the 38th parallel was communist North Korea, and south of the 38th parallel was South Korea, a democracy. On 25 June 1950, a very strong Russian-trained North Korean army invaded South Korea. It was equipped with a large number of T-34 tanks the Russians had used in World War II to defeat the Germans.

The United Nations met in emergency session to consider sending aid to South Korea. Russia could and would have vetoed the proposal, but Russia was boycotting the UN and the resolution passed. The United States immediately sent air power and occupation troops from Japan, but we were unprepared to fight against such a powerful army. Our WWII Sherman tanks were no match for the Russian tanks that had defeated the German Panzers, and our WWII bazookas were ineffective against them. It appeared that all of South Korea would be captured by the North Korean Army.

Short Honeymoon

Marines from every station in the world, as well as all reserves, were called to active duty. I received my orders to report to duty in ten days. I had been dating Belva Clare Hope for several months while she was in training as a cadet nurse at Methodist Hospital in Dallas. We decided to get married, and after a brief ten-day honeymoon, I reported for duty knowing almost certainly that I would be sent to Korea.

I left Dallas by troop train on 31 July 1950 and arrived at Camp Pendleton, CA where we were told there would be no liberty. We had two weeks to form what would become the 1st Marine Division. Reveille was at 0500 (5:00 AM), and our day lasted until 1800 (6:00 PM) in time for our evening meal. Taps was at 10:00 PM.

The division was formed in record time and set sail for Japan, stopping in Osaka to reload for combat. While in Osaka, a typhoon with winds of 110 miles per hour struck, and the plaster from the ceiling of our building began falling. We put on our helmets and waited it out.

Love Birds

We were given a liberty, during which Jim Johnson, George Bell and I — after a few drinks — bought a pair of love birds. After all, we were in Love battery and we needed a mascot. I remember it began to rain and Jim bargained with a Japanese woman for her umbrella. I can still visualize it today: three not so sober Marine Sergeants staggering through the front gate of our camp with one holding the bamboo bird cage and two trying to hold an umbrella over the cage to keep the birds dry.

Artillery

I was assigned as a crew chief of a 155mm howitzer, which was the largest in a Marine division arsenal. There were three batteries of six guns; each battery supported one of the three infantry regiments as needed. A 155mm projectile weighed one hundred pounds and was approximately six inches in diameter and eighteen inches long with fuse. It had a maximum range of nine miles. It used several types of fuses, but the most effective against personnel was the proximity fuse, which sent a radio signal. When it neared a target, the signal bounced back activating the fuse and causing the shell to explode about forty feet in the air, showering hundreds of shards of jagged steel down upon the enemy. Artillery is the most effective weapon in conventional warfare.

The UN forces were driven into a small perimeter at the southern tip of the Korean peninsula. The order was given to “Stand or Die.” Meanwhile, we had formed an invasion force consisting of the 1st Marine Division and the 7th Army Division for an amphibious landing behind enemy lines. I was destined to be a part of that invasion force. Our Howitzers were loaded aboard LST number QO72, a WWII LST (Landing Ship Tank), and we set sail for Korea.

I went from civilian to combat in six weeks.

Marines Shine Again

On 15 September 1950, I landed with the 1st Marine Division at Inchon, Korea, which is west of the capital city of Seoul, with some of the highest tides in the world. High tide could be 30 feet at night and by 10:00 the next morning it became a mud flat extending hundreds of yards. At first light I watched the battleships; planes and rocket ships bombarded the island of Wolmi-do in preparation for the invasion. Wolmi-do was separated from the port of Inchon by a causeway. The first waves of Marines were circling in their boats waiting for the bombardment to lift at 0800 when they were to go ashore. The Marines would be on their own, and it was imperative that they hold until the evening tide came in.

I had my doubts that one Marine Division and one Army division could successfully land behind enemy lines and defeat the North Korean Army. The Chief of Staffs also had their doubts, but General McArthur convinced them it could be done.

After a successful landing and the capture of Wolmi-do, General McArthur, observing from his flagship, made the comment, “Marines have never shined so brilliantly.” This saved the Marine Corps, as the Secretary of Defense was planning to eliminate the Corps.

Marines on Wolmi-do Island, 1950

Marines on Wolmi-do Island, 1950

While waiting for evening tide to go ashore, I remember wondering if the letter I was writing would be my last. We would be facing some of the best tanks in the world.

We did not go ashore until 10:00 the following evening. We could not emplace in the dark, but by early light we were in place and firing. The love birds were our first casualties; the concussion from the guns was too much for them. We awarded them each a Purple Heart and one battle star.

For some Marine reservists, it was the first time to see a howitzer fire. We were ill prepared. One young reservist, who had not gone through boot camp, was assigned to the tanks. He asked, “How do I get into it?”

Fortunately, General McArthur was right: landing at such an unlikely place for an invasion caught the North Koreans by surprise. By cutting across the middle of the peninsula it cut the North Korean army’s supply lines and changed the tide of the war.

Fire Missions

Fire Missions

Our forward observer reported the results of most fire missions. We had placed direct hits on a train, three enemy tanks, a truck convoy, and enemy troops. Later we seldom knew our targets, except when we were using air bursts when we knew our targets were troops. As we advanced, we could see the devastation caused by artillery.

Occasionally we received counter battery fire from enemy artillery, but we had a crude method by today’s standards of locating the source and eliminating it. We only lost one gun from enemy artillery, and that was after I had left the war.

Our tanks were the new M26 Pershing tanks, which were superior to the Russian T-34 tanks. In addition, a new more powerful bazooka had been rushed to production. The new bazooka was used for the first time to knock out four Russian T-34 tanks on the road heading to Inchon from Seoul. In a matter of days Seoul was captured. I had now changed my mind about who would be the victor in this battle.

We entered Seoul in the middle of the night, but we could see by the light of a full moon the devastation and rubble. We could also see the royal palace where General McArthur officially returned South Korea to its president, Sigmund Rhee, on 25 September, three months to the day from when North Korea invaded South Korea. When the North Korean Army found that they were isolated in South Korea, they abandoned their equipment and made their way back to North Korea.

Pursuit

With the defeat of the North Korean Army, General McArthur requested permission from the United Nations to pursue the Korean Army into North Korea and unite the two Koreas into one nation. Permission was granted, and UN forces crossed the 38th parallel into North Korea. The 38th parallel had been the dividing line between the two nations. I had earned my third battle star and was about to go after a fourth. Saipan was my first, Okinawa was my second, and Inchon was the third.

We embarked aboard the QO75 at Inchon to make an amphibious landing at the important oil port of Wonsan on the East coast about half way up North Korea to cut off the retreating North Koreans. We found we could not land because the Russians had mined the harbor so heavily that it took our mine sweepers ten days to clear it at the loss of, I believe, three mine sweepers.

Unable to land, we sailed up and down the coast for ten days waiting for the harbor to be cleared. It was called Operation Yo-Yo. We virtually ran out of food, and because water was rationed, we were served one cup of black coffee three times a day. It was then that I learned to drink my coffee black.

When we finally landed, it was the most embarrassing moment in Marine Corps history. The Marines were greeted not by the enemy, but by Bob Hope!

We were issued long underwear, wool shirts and trousers, a fur lined vest, water-resistant outer trousers, heavy mittens with a thumb and trigger finger, a fur lined parka, two pairs of socks, rubber boots called shoepacs that had a thick felt insole to absorb perspiration, and a down sleeping bag.

The 1st Marine Division advanced from Wonsan to the port of Hamhung, then inland to within thirty miles of Manchuria up a primitive mountain road into the mountains on the east side of the Taebeck Mountain range that divides North Korea. Almost all of Korea was now under control of United Nations forces.

“Volunteers”

The 7th Marine Regiment had been attacked by a Chinese division that was decimated by the Marines. The Chinese General had observed the battle with field glasses, as he was actually testing the Marines ability to fight. Prisoners taken from three divisions made Marine General O.P. Smith realize they were not “volunteers,” as MacArthur’s headquarters in Japan had characterized them. But then the Chinese disappeared. General McArthur announced that we would be home for Christmas!

China had warned the United Nations to stop fifty miles south of the Yalu River, the border between Manchuria and North Korea. McArthur assured President Truman that the Chinese would not enter the war, and he ignored the Chinese warning. Our Army Generals arrived at the Yalu, and in a ritual act of defiance urinated into the river in plain sight of the Chinese and Russians watching from across the frozen river. What the generals did not know is that hundreds of thousands of Chinese had already walked undetected across the frozen Yalu River into North Korea.

Marine General Smith openly refused to obey orders to drive hell-bent to the Yalu River, and he ordered an airstrip be built at Hagaru-ri, as well as stockpiling ammunition and supplies. He ordered his regiments to proceed with caution. He wrote the Commandant of the Marine Corps about his concerns with the Army’s failure to recognize the evidence of a strong Chinese presence.

While on a patrol searching for Chinese “volunteers,” we were in a column going up a hill when a doe came over the crest running parallel to the column. A dozen Marines opened up with automatic weapons, but in their haste forgot to lead the Doe. On our way down, we encountered a company of Marines. They had heard the firing and asked if we had been in a firefight. When we explained, the Captain asked, “Where is the deer?” Upon learning we had missed, he said, “It’s a dammed good thing you did not run into any Chinese!”

Blocks of ice began flowing down the Imjin River, and on Thanksgiving Day it was zero degrees. Our Thanksgiving dinner froze before we could eat it. I had not had a shower in two months, so I decided that despite the cold I would jump into the fast flowing water and rinse off. I hardly stayed long enough to get wet.

Changjin Reservoir

We moved up onto a 4,000-foot plateau in the Taebeck Mountains over a narrow primitive mountain road, through the village of Koto-ri to Hagaru-ri. Here the road divided to each side of a reservoir named Changjin that became known as “Chosin,” the Japanese pronunciation.

The 7th Marines went west over a 5,000-foot mountain pass named Toktong to the west side of the reservoir to a village named Yudam-ni. The 5th Marines proceeded to the east side of the reservoir. The division was now strung out over a distance of 75 miles from the seaport of Hungnam and 30 miles from Manchuria. Separated and scattered into small groups, the 1st Marine Division was now in the position the Chinese had been waiting for.

However, an unexpected event happened: 3,000 soldiers from the 7th Army Division arrived on 27 November to relieve the 5th Marine Regiment, which then managed to join the 7th Marine Regiment on the west side of the reservoir just hours before the Chinese planed attack. This was a move the Chinese had not anticipated and one that probably contributed to our survival. The 5th and 7th Regiments, together with the 4th Battalion of the 11th Regiment artillery, was now a stronger force on the west side.